In search of the strange

Hi, friends.

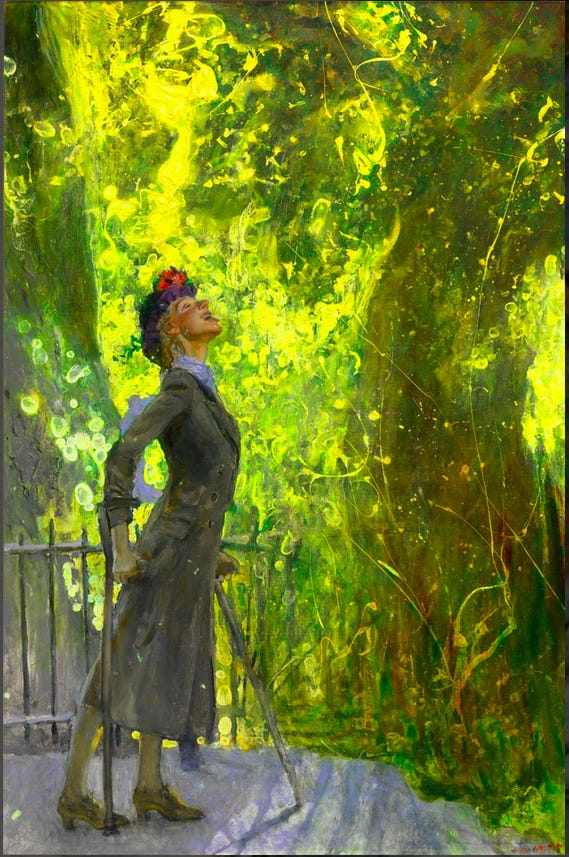

The great pollening is upon us. Somehow, it collects between downpours, and transforms everything into a bright, yellow crime scene. Everything that was familiar, transformed for a week or so.

And so, I want to talk a little bit about weirdness. When I was learning to write, almost all the stories held up as models were rooted in realism. (An Alice Munro offered as an answer for Carver and Ford and other assorted minimalists. The only experimental piece I can remember is Coover’s “The Babysitter.” It was not a piece I wanted to think about again much less emulate.) The work I wrote during that time period feels pretty meh to me now. Most of it rejected by a long list of lit journals. But I kept reading, and writing, and figuring things out. And slowly, some weirdness started creeping into my work. It made the writing sharper and more interesting.

If there’s any lesson we’ve learned this year, isn’t it that the world is actually full of weirdness? Maybe your work needs a little bit of weird too.

Story.

I’ve got three little stories for you with different strands of strange in each: By the Gleam of Her Teeth, She will Light the Path Before Her by Tina May Hall. The Invasion from Outer Space by Steven Millhauser. A Room with Many Small Beds by Kathy Fish.

Craft tidbits.

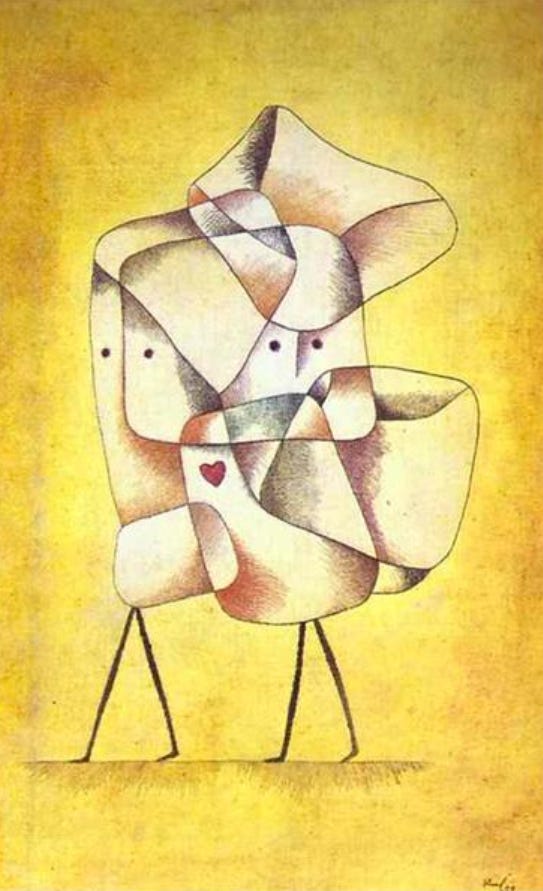

The technical term for this weirdness is defamiliarizaiton. It simply means to make the familiar strange, and the strange familiar. Predictable characters in predictable settings create familiarity. Sometimes we want that. There’s a comfort in watching a television show that we’ve already seen. The familiar can be a friend. A hand to hold, especially when our lives are unsettled. But it can also feel flat. It can leave us bored. Uninspired. Craving more. I would argue that the art we remember is art that is new and surprising - whether that be a film, a painting, a song, or a story.

By the Gleam of her Teeth is delightfully unsettling. There are echos of fairy tales here, deep in the woods, where no one has a name: Father, Mother, First Daughter, Second Daughter, Only Son.

These details create some weirdness, as does the grandmother’s ghost. It’s not just the inclusion of the ghost. But it’s her actions too. She tries to chew through the rims of cans in the kitchen. (Which seems difficult for a ghost?) She bites the Only Son’s arms. First daughter is obsessed with burning things in the fireplace. There is someone outside rummaging through the woods with a flashlight. Mother mistakes it for the moon. Or maybe she hopes it is an ax murderer come to relieve them all of this life.

One way that Hall creates srangeness is giving inanimate objects wants and needs. She does this here and in her novel, The Snow Collectors. Here, the origami napkin swan watches the family. And

In the garden, rows and rows of green beans tangle closer for warmth. The eggs in the henhouse mutter in their sleep.

Millhauser, on the other hand, gives us an out of the ordinary event - this yellow dust that descends upon them and multiplies without rhyme or reason. But the language here is pretty predictable.

We were urged to remain calm, to stay inside, to await further instructions.

It’s a we story. And the population behaves pretty predictably. They wait. And watch. Just as they’ve been told to do. And in this waiting, their desire to witness something terrible grows. In fact, they are disappointed in the yellow dust.

We had wanted blood, crushed bones, howls of agony.

But Marsha, you say, that’s not how people would behave. This would not happen. Who roots for chaos? Um. Look around? Last week people were angry all over Alabama because the threat of tornados did not materialize as forcasted. People were rooting for the tornadoes! The chaos. The destruction. I mean. Really.

The other nice thing Millhauser’s doing here is on the sentence level, creating a kind of breathlessness at the beginning with run-on after run-on. It disappates once the destruction comes. In fact, in the section that details their disappointment, six sentences in a row begin with “we had wanted.” They are stuck in a loop with these wants that did not materialize.

In A Room with Many Small Beds, we have a young girl trying to navigate life with father’s girlfriend. While the situation might be familiar, the character here is precocious and unpredictable. She tells us at the beginning that

It is the year I learn to float.

Not in water as one might supose, but levitate. To float away, presumably like the moths she eats. (Yeah, that’s right. She eats them.)

Too, the segmented form allows the reader make connections. And they want to do that. It makes them feel smart. In the second section, we’re told Pearl looks like a sea creature with rollers in her hair. In section five, her arms become tentacles. Here, Fish is using interesting imagery to make comentary on what the narrator thinks of Pearl. A reminder to us to reach for those new metaphors.

Sparks.

Another way to bring in weirdness is through landscape. A forest where all the trees have teeth, for instance. Where flowers are made of ice. Where the river is… you get the gist. (I should note, it need not be sinister to be weird. One night when I let Maisey out, we discovered someone had tossed dog treats all over the backyard. A night I am sure she fondly remembers as the Miracle of the Milkbone. What weirdness have you witnessed?)

Or. Have you ever written a “we” story? It’s a fun way to think about the collective nature of character. This could be a family, a team, an office. A town, a church, a cult.

Revision prompt: Maybe you have a story that has a pretty predictable scene. People behave in the way that seems logical. But maybe they shouldn’t. Maybe that’s why the story, chapter, essay isn’t working. Brainstorm other ways they could behave. How would that add some life to things?

Other tidbits.

A few newsletters ago, I mentioned Matthew Salesses’s Craft in the Real World. He’s giving some talks on rethinking workshop. I’ve signed up for one of them. Here’s one that’s free.

PBS has a new documentary on Flannery O’Connor. [My favorite lines from a Good Man is rooted in weirdness:

The trees were full of silver-white sunlight, and the meanest of them sparkled.

There is also the strange, unexplained monkey in the Chinaberry tree at the BBQ joint.]

The Oxford American has a call for short stories, flash, and essays about Southern writers and literary community.

I’m reading a book set in India right now. If you would also like to spend your afternoon in a foreign land, Trip Fiction lets you search for works by location. (It looks like it’s not just limited to fiction.)

Okay, Scribblers. That’s all I’ve got for today. I hope spring is finding you all and reinvigorating your writing life. If you know someone who might also like what we’re doing here, I’d really appreciate it if you’d foward this to them.

Happy writing~

Marsha